![]() As dramatically imperfect as U.S. fisheries management can be, I still stand by my stance that we have the best-managed fisheries in the world. Fishermen gripe about it being too restrictive and quick to change, conservationists complain about it being too lenient and slow to adapt, and both have a point. That said, we could do much worse than the job NMFS is doing. This is especially true for shark and ray fisheries, where the old practice of lumping all but a few species into one of two “coastal shark complexes” is giving way to species-specific management. This is perhaps most dramatic for the scalloped hammerhead, which is finally getting its own stock assessments and may be headed for Endangered Species listing. We’ve come a long way since crashing the Atlantic cod population. But not every country does as good a job as us…

As dramatically imperfect as U.S. fisheries management can be, I still stand by my stance that we have the best-managed fisheries in the world. Fishermen gripe about it being too restrictive and quick to change, conservationists complain about it being too lenient and slow to adapt, and both have a point. That said, we could do much worse than the job NMFS is doing. This is especially true for shark and ray fisheries, where the old practice of lumping all but a few species into one of two “coastal shark complexes” is giving way to species-specific management. This is perhaps most dramatic for the scalloped hammerhead, which is finally getting its own stock assessments and may be headed for Endangered Species listing. We’ve come a long way since crashing the Atlantic cod population. But not every country does as good a job as us…

A paper recently published by my labmate Andrea Dell’Apa summarizes the issues with fisheries management in Italy, a system he’s familiar with from, well, living and working there. Like most countries on the Mediterranean Sea, Italy has some real issues managing its fisheries effectively.

Right off the bat, Italian fisheries management has a real problem with managing species as “species complexes.” The issue with managing species in complexes is that species with wildly different life histories (and therefore tolerance to fishing pressure) end up managed as if they were all the same population. This is often due to species co-occurring so often that catching one is impossible with bycatch of the others (as with our snapper-grouper and New England groundfish complexes) or difficulty in telling the species apart (as with the Carcharhinid species in the large and small coastal shark complexes). For the elasmobranch complexes in the Italian fishery, it has everything to do with elasmobranchs being second-class fish.

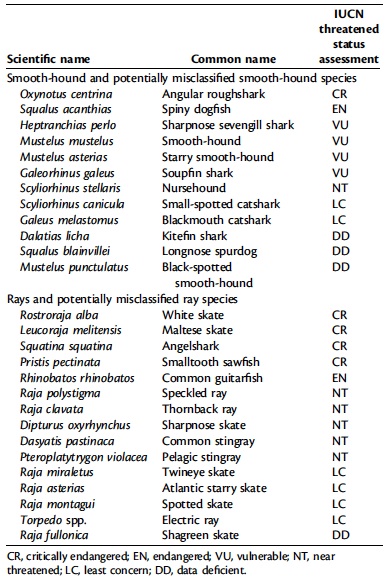

All the species landed as "smoothhounds" and "rays" in the Italian fishery. From Dell'Apa et al. (2012).

Even here in the U.S., all sharks were once reported as just “sharks.” In the Italian fishery, elasmobranchs are classified based on their physical resemblance to the most commonly-landed species. The small sharks landed are all classified as “smoothhound” (sharks in the genus Mustelus, such as the smooth dogfish) while all skates, rays, and flat sharks are classified as “rays” (supposedly all members of the Raja genus). So basically, as far as any official accounting goes, any elasmobranch caught in the Italian ground fishery is either “something that looks like a smoothhound” or “something that looks like a ray.” As you can see from the table at left, these complexes include species that run the gamut of IUCN population statuses. This includes some of the world’s most endangered spiny dogfish, angel shark, and skate populations, as well as several deep sea species we don’t know enough about to even guess whether they’re overfished.

By comparing landings to the timing of fisheries management policies, Dell’Apa et al. (2012) were able to make some interesting connections between policy and the fate of Italy’s “smoothounds” and “rays.” Until 1982, small sharks and rays were largely bycatch species of little value to fishermen. However, after the 80’s elasmobranch landings skyrocketed and quickly showed the boom-and-bust pattern familiar to anyone looking at an unregulated fishery (especially one for sharks). So what happened in 1982? Italy passed Law 41/82, the “Plan for the Rationalization and Development of the Commercial Fishery,” essentially the Italian equivalent to our Magnusen-Stevens Act. This law imposed more conservative quotas, gear requirements, and required licenses for many bony fish species, but pretty much ignored elasmobranchs altogether. As a result, a completely unregulated fishery for elasmobranchs erupted, collapsing the populations of dogfish-sized sharks and skates within 10 years. It’s even possible that a lack of smaller sharks to prey on may have been a factor driving many of the larger shark species out of the Mediterranean.

Fisheries management is complex and often rife with unintended consequences. In many ways, you can’t blame European countries for having such chaotic and insufficient management. The Mediterranean has been fished since the dawn of major human civilization, so it’s impossible to know what the true, unspoiled baseline fish populations would be. Add to this the sheer number of sovereign nations bordering the Sea, some of which may be at war, and it’s no wonder the Mediterranean is in such ecological dire straits. In the U.S., we have it comparatively easy, with many of our fish stocks staying within our waters, a friendly neighbor to the north, and a usually-friendly neighbor to the south. I don’t envy European fisheries managers.

In conclusion, our fisheries management is far from perfect, but could be much worse. USA! USA! USA!

References

Dell’Apa, A., Kimmel, D., & Clo, S. (2012). Trends of fish and elasmobranch landings in Italy: associated management implications ICES Journal of Marine Science DOI: 10.1093/icesjms/fss067